FAR AND WIDE

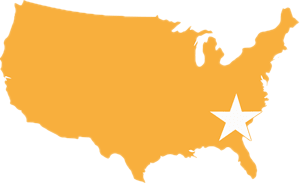

The initiative to find common purpose began in four towns spread around the country. They were chosen because they are very different in their nature and in their politics, and because they are each emblematic of something bigger than themselves.

Why small towns? They are observable in a way that cities are not. Rather than being absorbed into some amorphous urban sprawl – their distinctiveness lost – small towns are set apart, entities onto themselves. The values of the people who live in each of them are pretty well set out. Residents might not know everyone else by name but they know all the faces. It’s pretty hard for anyone in town to hide.

For this exercise, I particularly zeroed in on a small group of individuals – 14 spread across the four towns – who are prominent members of their respective communities. They come from many walks of life – educators, owners of small businesses, attorneys, developers, a judge, a newspaper publisher. They are different from each other on the various dimensions by which we all differ, and yet each is very much an American.

They kindly sat for many hours of examination about what it means to live in this country, in the process providing a window on how their beliefs are influenced by their own life experiences and by their surroundings.

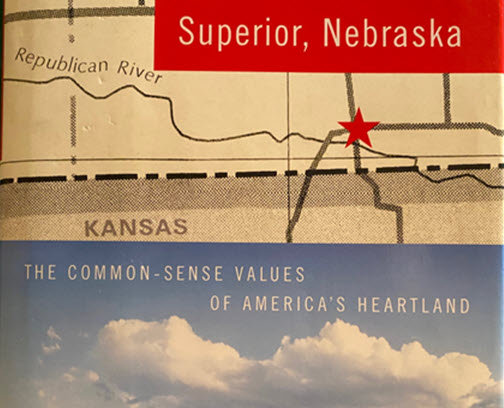

SUPERIOR, NEBRASKA

The farming community of Superior sits smack dab in the middle of the country. East-west, it’s within 50 miles of halfway between Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. North-south, it’s almost precisely halfway between International Falls and Galveston.

More to the point of this inquiry, it’s also right in the middle of the nation’s heartland. Situated almost atop the Nebraska-Kansas state line, Superior is surrounded by 150 miles of corn and soybeans that separate the two important interstate highways – I-70 and I-80 – slicing east and west across the heartland.

It’s enough off the beaten path that locals can’t remember being visited by any of the succession of congressmen who have represented rural Nebraska. Townsfolk can live with that. What riles them here in nameless, faceless flyover country is that their fellow Americans living on the coasts will never get closer than 35,000 feet overhead.

Remote as it is, Superior can nonetheless claim to be right in the thick of conservative tendencies, having served as the centerpiece of a book aptly titled Superior, Nebraska: The Common-Sense Values of America’s Heartland. Coincidentally but quite appropriately, the waterway on the edge of town is named the Republican River.

Like a lot of towns across rural America, Superior struggles mightily today to sustain itself as farms are corporatized and manufacturing disappears. While this is of considerable concern, at least some of the locals maintain that big paychecks aren’t at all necessary to revel in the “million-dollar lifestyle” of their rural setting.

AJO, ARIZONA

Ajo, a dusty enclave in the middle of the hot Southwestern desert, got its start as a copper mine and the company town that grew up around it. When the company pulled out in 1985, it left a big hole in the ground and an even bigger hole in town.

Ajo is the Southwest equivalent of the Rust Belt: Abandoned open-pit mine, useless slag heaps shaped into flat-topped mesas, rusting works, once proud union members without jobs. In this case, with no local government to lend a hand.

Scratching out a living isn’t easy. The hardscrabble setting is surrounded by a vast Indian reservation, an Air Force gunnery range, a wildlife refuge, and an extensive national monument devoted to a particular variety of cactus.

Just south of the national monument, 40 miles in total from Ajo, is Mexico. Much of the activity in the area is provided by the Border Patrol looking for drug smugglers and migrants, and construction crews there to build the wall.

Ajo is making do. Its once segregated population of Caucasians, Hispanics and Native Americans has banded together in an effort to rehab and repurpose the town, for instance with the Curley School shown above. They get a much-needed boost from an annual influx of winter residents from the North who have discovered Ajo is much less expensive than other ritzier destinations in the Sun Belt.

CONCORD, MASSACHUSETTS

Concord has been an iconic town in America ever since Paul Revere headed there on his famous Midnight Ride. “The British are coming! The British are coming!,” he – or more likely, one of his compatriots – cried out.

Incorporated in 1635 as one of the earliest settlements in the New World, Concord was for several centuries a farming community and mill town. It took on a learned air in the mid-1800s when a remarkable circle of local intellectuals – Thoreau, Emerson, Alcott and Hawthorne – rose to national prominence.

Incorporated in 1635 as one of the earliest settlements in the New World, Concord was for several centuries a farming community and mill town. It took on a learned air in the mid-1800s when a remarkable circle of local intellectuals – Thoreau, Emerson, Alcott and Hawthorne – rose to national prominence.

Over the years Concord has gone from a rural outpost to what today would be called an exurb. The trains that rumbled by during Thoreau’s stay at Walden Pond today whisk commuters from Concord into Boston and Cambridge. Their proximity makes Concord much less isolated and much more prosperous (to the tune of $100,000 more annually per household) than the other towns represented here.

Concord is closely tied to Boston and Cambridge in another regard. The political tendencies of eastern Massachusetts are as liberal as anywhere in the land.

EDGEFIELD, SOUTH CAROLINA

Politics and race are the two primary calling cards of Edgefield, which has had an outsized impact on one of the most adamantly conservative of states.

Even with a miniscule population, Edgefield is proud to have been home to 10 governors of South Carolina. Nine of those served in the 1800s. The tenth, Strom Thurmond, was elected in 1946. Two years later he became the presidential nominee of the States’ Rights Democratic Party, otherwise known as the Dixiecrats, in its bid to perpetuate racial segregation.

That’s not all the history from this one little town! Edgefield also was home to several major figures in the impasse between the North and South, and scene to major standoffs over reconstruction and desegregation. “We have a long tradition of having a relatively small number of very outspoken people,” observed one of the participants in this project.

The history is not as one-sided as it might sound. Blacks have had their victories along the way, including in one dispute that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Edgefield, located on the western edge of the state just across the Savannah River from Augusta, Ga., has struggled on the economic front as farm jobs diminish and textile manufacturing disappeared entirely. The biggest addition in recent times is the federal prison that Strom Thurmond brought to town late in his long career as a U.S. senator.