Political Strife Can Be Laid to Conflicting Values

Part IV of a series March 9, 2025

One of the biggest aha moments in the early field work for Our Common Purpose came in a small farming community in very rural Nebraska. I had been drawn there by a book that claimed the town of Superior possessed the “common sense values of America’s Heartland.”

The subject being discussed in a lengthy discussion with a couple of town leaders was equality. The participants readily agreed that everyone deserves equal opportunity. However, in a small town where everyone knows everyone else’s business, they weren’t willing to let the subject go at just that.

For starters, they wanted it known that the folks of Superior don’t judge each other by the color of their skin but by their contributions to the community, to the extent they are able. And what really galled them was that while the great many busted their butts, some did little more than sit on their duffs. The offenders had drifted into town because housing was dirt cheap, and otherwise they lived off public assistance. To be clear, these assertions were not being made about people of color.

The clash over what should be regarded as fair and equal was one of the formative moments in my early work on Our Common Purpose.

It closely parallels, albeit on a much smaller scale, the earlier experience of social psychologist Jonathan Haidt as he went about developing the moral foundations he explores in his seminal work The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. He and his colleagues were forced to make a major revision to their initial list of moral foundations due to conservative pushback over exactly the same point. As Haidt describes it, “fairness, which focused on proportionality, not equality.”

These conflicts occurred long after the death of Isaiah Berlin (in 1997) but he wouldn’t be a bit surprised. In fact, he fully anticipated it.

His theory of values pluralism, on which Our Common Purpose’s study of American values is based, pre-supposes that our values, even our most cherished ones, do not exist in isolation. Inevitably they come into contention with one another. We cannot have all of one and at the same time have all of the other. By some process we have to choose how much of the one we want and how much of the other we are willing to sacrifice.

Such tradeoffs escalate the tension we are already feeling toward values that are conflicted or partisan in nature, and even send a shudder through some of our rock-solid convictions. Its effects have an ongoing impact on American society in general and political strife in particular, and yet this incredibly important phenomenon almost always goes unrecognized and unexplored.

Taking a few exploratory steps toward expanding our understanding is the primary purpose of this study of American values, what about them unites and divides us, and what we might do about it. The results are based in good part on a nationwide public opinion survey focusing on 25 key American values done in September that furnishes numerical evidence for what otherwise has been theory. The 2,500 respondents, who mirror the characteristics of the nationwide voting population, were asked by Survey USA to answer a lengthy set of questions using a sliding scale of -100 to +100.

The differing interpretations of fairness provide a vivid illustration of how our values come into conflict. The common interpretation of equality could be defined as “fair and equal treatment.” That phrase actually scores better in this survey than when “equality” is summed up as a more open-ended, single word.

The differing interpretations of fairness provide a vivid illustration of how our values come into conflict. The common interpretation of equality could be defined as “fair and equal treatment.” That phrase actually scores better in this survey than when “equality” is summed up as a more open-ended, single word.

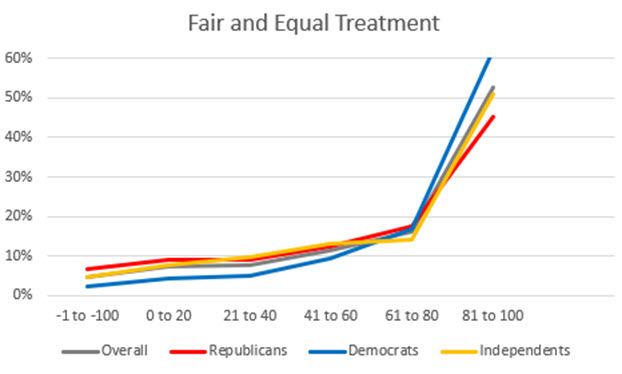

High percentages of each political persuasion think “fair and equal treatment” is very important. Few give it a negative score. It does, however, fall into the category of Conflicted Values because Republicans don’t rate it quite as highly as do Democrats, in particular those who regard themselves as “very liberal.”

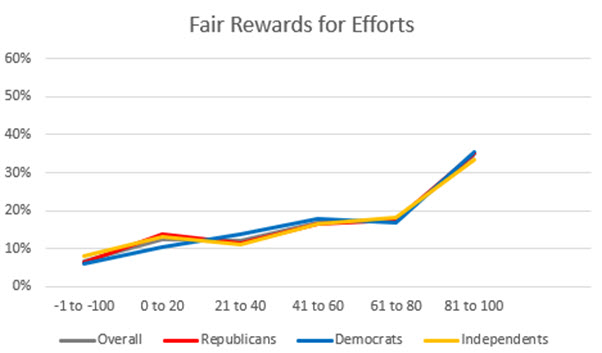

The competing definition of what’s fair that arose in Superior might be labeled “fair rewards proportionate to effort.” This value is regarded as very important by smaller percentages but the distribution of scores  is remarkably consistent across all demographic divisions. Republicans, Democrats and independents are almost exactly the same. Even more remarkably, “very conservatives” and “very liberals” score it almost equally.

is remarkably consistent across all demographic divisions. Republicans, Democrats and independents are almost exactly the same. Even more remarkably, “very conservatives” and “very liberals” score it almost equally.

In isolation, each of these values stands nicely on its own. The trouble starts when the two come into conflict – such as happens officially in determining eligibility for assistance programs and unofficially in how the public reacts to those programs.

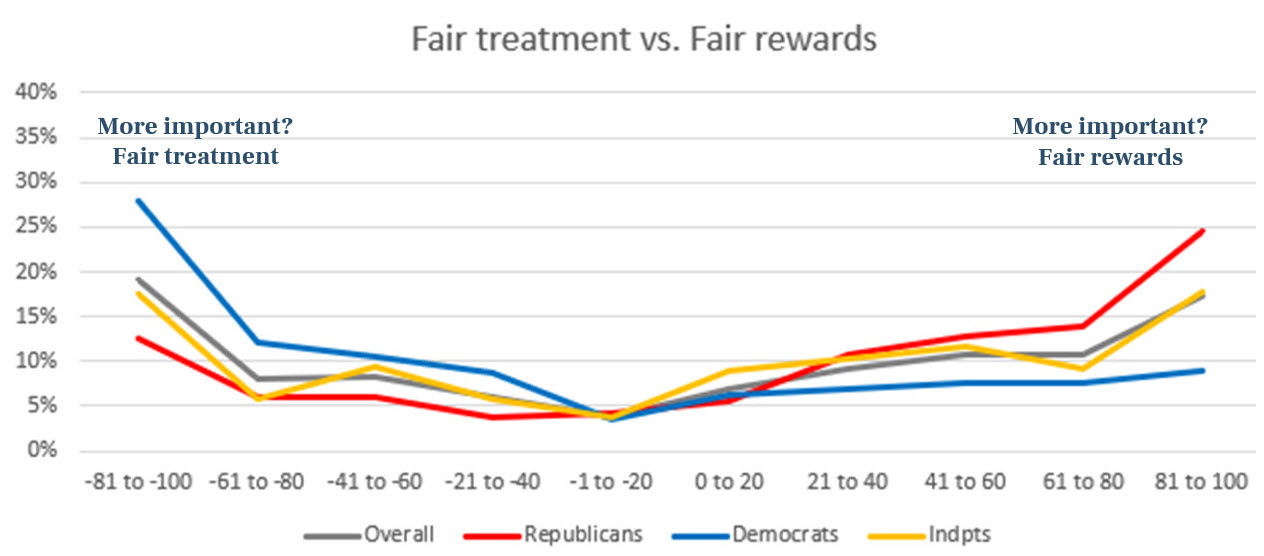

When folks are asked in this survey to choose between fair treatment and fair rewards, things go haywire. The relative agreement on the values individually turns into disagreement on how to prioritize the two. And the differences are not just between political persuasions; there are divisions within.

Scores in the middle would indicate that respondents are torn between the two values, and are trying to balance the two. Surprisingly few chose to do that.

Instead, they tended to fully support one value or the other. More Democrats went all-in on “fair and equal treatment” but there’s also a number who went in the other direction. More Republicans went all-in on “fair rewards proportionate to effort” but there’s also those who went the other way. And independents, who might be most expected to balance the two, also chose one or the other. In their case, they divided almost equally as to which they preferred.

Faced with choosing which of these values best represents fairness, it turns out we don’t agree. This is more than an academic exercise. It reflects the division we experience in real life.

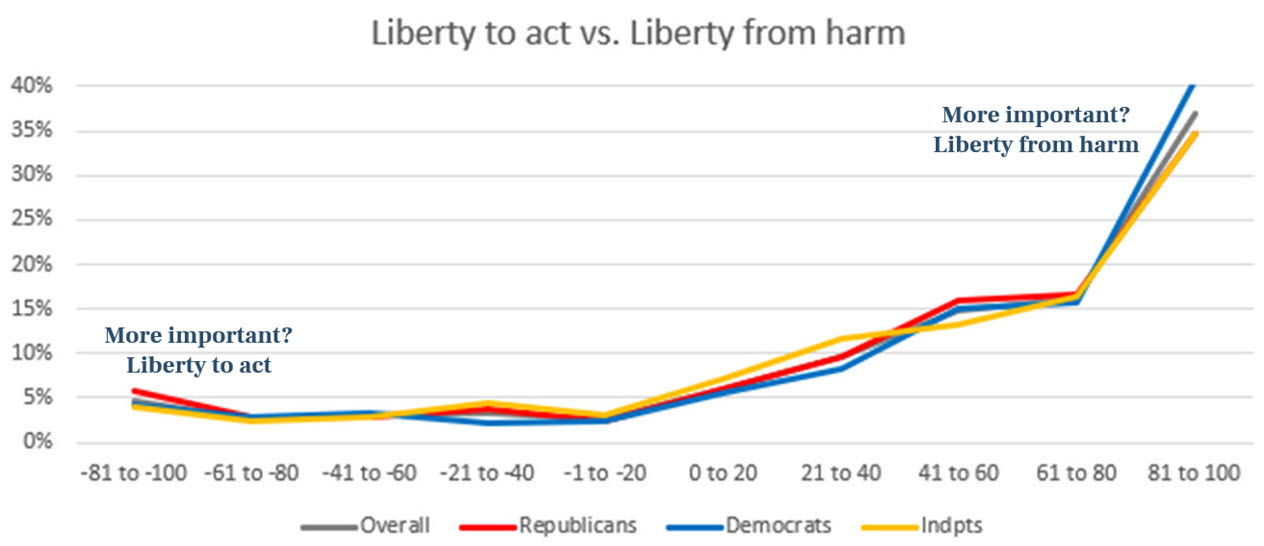

Looking across the array of conflicts, this is not always the case. One notable exception comes under the heading of liberty. Isaiah Berlin was himself fascinated by the several ways that “liberty” can be interpreted and applied. Those intricacies do not bear discussion here but the one distinction that frequently arose in the field was the separation between our liberty to act versus our liberty from harm.

Several participants in the initial interviews long ago spontaneously raised an old adage: “My right to swing my fist ends at the tip of your nose.”

One might guess Republicans would trend in one direction on this, Democrats in the other. That turns out not to be true. There’s broad consensus across party lines that liberty from harm takes precedence over liberty to act.

In most cases, however, the survey confirms that Isaiah Berlin’s suppositions were correct. Values come into conflict with one another. When they do, likely as not our response is divided.

— Richard Gilman

Next: Applying This to Today’s Issues

Part I: Our Key Values Both Unite and Divide

Part II: Some Values Get More Regard than Others