New 3rd Party Is Best Bet for Polarity Thinking

Final installment, Part IX of a series, June 1, 2025

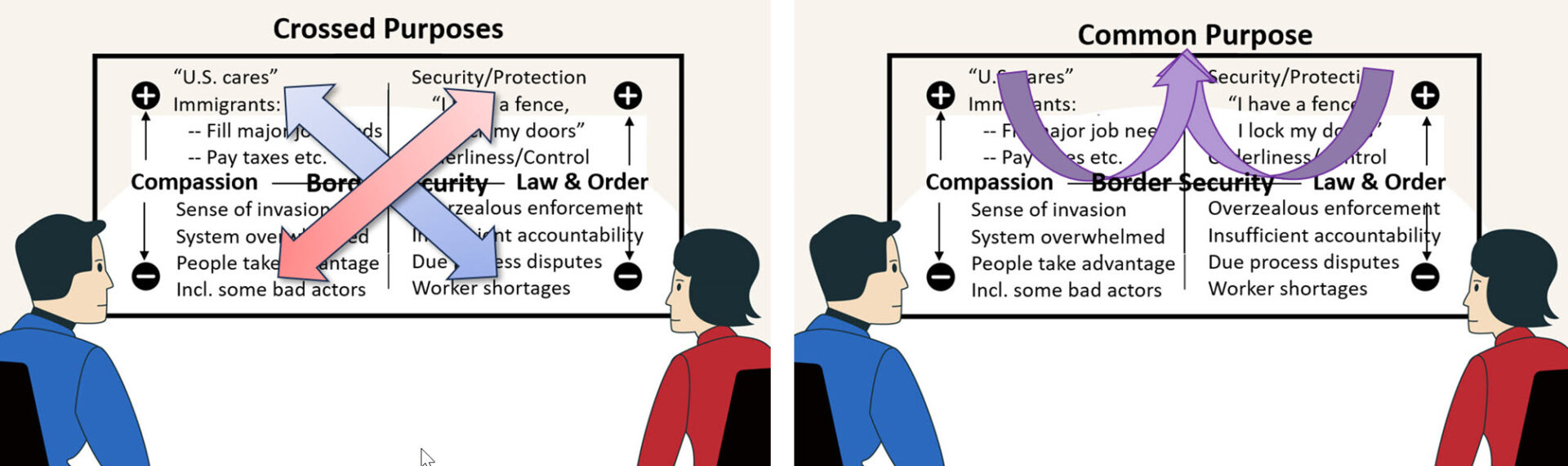

The thousands of words written here about American values uniting and dividing us could be boiled down to this: We need to get from “X” to a “w”.

This final installment of a series that began in January offers reflections and recommendations, but first to recap what we’ve learned:

Consistent with the theory of values pluralism put forward long ago, even our most cherished values inevitably come into conflict with each other. The million-, billion-, trillion-dollar question is the method we choose for dealing with those conflicts.

How we mismanage them today is readily depicted by the X. We literally are at cross purposes with each other.

The two political parties eagerly encourage our primeval instincts of discerning friend or foe. One party promotes the positive side of its remedy to any conflict and castigates the negative side of its opponent’s approach. The other party does just the reverse, promoting its own positives and lambasting the opposition’s negatives.

It’s either/or. Either you’re for our approach or you’re against it. The same goes for the other side. The X is not collaborative, it’s confrontive.

In reality, neither side has all the answers. One side’s approach is not the “problem” and the other the “solution”. Polarity management, the method of thinking that has come front and center in this series, posits that any two conflicting approaches, any two conflicting values, each have their upside and their downside.

This leads to an overarching observation that cannot be overstated. We need to fundamentally re-orient our thinking.

Rather than fixating endlessly on the vertical axis of left versus right, we need to focus instead on the horizontal axis. Up versus down. What are the positives of